Take It to the Limit

Hi! It's been a hot minute but here's the second installment of the Boundaries newsletter. If you'd like to read the introduction, click here. If you're not yet subscribed, sign up here. Thanks for your support so far!

Putting a Limit on Boundaries: The Lesson of Concept Creep

When I began imagining the ways that boundaries show up in our lives and throughout history, I noticed a tendency in my own way of thinking that was a classic example of poor boundaries. My fledgling concept of boundaries had an overly porous boundary, like a gold panner’s sifter strung with chicken wire instead of tight mesh. It let too many dumb-as-rocks ideas pass into my proverbial pan, along with some flakes of wisdom. I was seeing everything as a boundary; my personal definition of a boundary was at risk of becoming boundless. This tendency has a name, and it’s an especially important one for mental health specialists like me to be familiar with: concept creep.

Like mission creep, the gradual broadening of the original objectives of an operation or organization, concept creep occurs when an idea or term encompasses too much. Good ideas have an inherent moral hazard: in their original form, they are striking because they succinctly communicate something interesting or important in the world. They become popular because of this ease of use, with various communities stretching and experimenting with different examples and settings where the idea might apply. Sometimes this helps evolve and strengthen the idea, but other times it adds too much noise to the original signal. Good ideas risk becoming gobbledygook.

The paper that originally coined the term highlighted six concepts in psychology that have had creeping expansion in their definitions and usage: abuse/neglect, bullying, trauma, mental disorder, addiction, and prejudice. This drift in the definition or meaning of a concept can have both positive and negative impacts. A write-up of the paper in The Atlantic points out that increased sensitivity to childhood neglect has sensitized society to the harms done to children by secondhand smoke and other exposures. At the same time, children’s playtime and their parent’s free time have both been eroded by fears that letting a child walk to school or play alone could be seen as neglectful, even though child abduction is just as rare as (or rarer than) when these activities were commonplace (prior to a 1980s panic about abduction that bred “stranger danger” into the fabric of suburban society).

The overdiagnosis of psychiatric disorders, from ADHD to depression to psychosis, also reveals the pros and cons of mission creep. A “big tent” approach to mental illness (wherein at least a quarter of Americans qualify for a diagnosis in any given year and almost half of Americans will qualify during their lifetime) can be a godsend that opens up meaningful resources and treatment to some people who might otherwise be missed. But it's also led to overtreatment, neglect and harm to others, whose inattention, sadness, or altered experiences require attention to social and economic problems rather than clinical diagnosis. In this case, the concept creep of “mental disorders” diverts political willpower, funding and policymaking away from the compelling structural factors that explain human suffering. As The Atlantic points out, “concept creep exacerbates failures to communicate.” We believe we are talking about mental health when we talk about psychiatric diagnoses, and yet this is a little like believing we are talking about birds if we name the different colors they come in.

So, how does concept creep apply to the exploration of boundaries?

My goal is to stretch the imagination around pressing issues that are near and dear to me: health and wellbeing, the climate crisis and the corporate plundering behind it, and the relationships amongst the many identities we wear as biological, ecological, social and historical beings. That’s a huge purview of personal interest, admittedly. But it does have its limits; this project is not aimed at administrative, clinical or legal transformation, in the way the aforementioned psychiatric disorders become formalized in academic research, clinical practice, institutional policies, and insurance reimbursement. My main aim is to communicate, to get more good ideas onto the page, where they transmit both information and the pleasurable sensation of engaging a familiar world in unusual ways.

The concept creep that I’m trying to reign in here, while searching for that just-right Goldilocks’s zone that is neither too broad nor too narrow, is what constitutes a boundary and what distinguishes it from a limit.

Boundary/Limit

Self-help literature and psychologically-minded content on social media is full of guidance for “setting healthy boundaries,” the most vague of these which celebrates either the majestic Power of Yes or the magical Power of No. Much of the time, setting healthy boundaries seems to be guided by this general rule: reclaim an ability to say no to certain invitations, requests or demands, while seeking more places where our identities and passions get an enthusiastic yes, whether that’s acceptance into a job opportunity, a social group or your own nuclear family. In the wrong hands, though, these instructions amount to “No for me, and Yes from everyone else.”

I will consider boundaries a bit differently in this project. A boundary is a place that leverages life’s inherent uncertainty to forge relationships between things that can evolve together rather than fight for survival. Our modern viewpoint is accustomed to considering relationships as a string of events, each one modeled after a commercial transaction where there is an exchange (of our labor, our attention, our time) between independent entities. We can cut or tie off that string, sometimes in the spirit of “healthy boundaries.” Maintaining boundaries then becomes a process of counting an emotional Rosary. I’m not throwing any shade on this process, which can be very helpful in abusive or toxic relationships. But compare this beads-on-a-string basis to another craft metaphor: weaving.

Weaving predates humans by millions of years: weaver birds do it (thank you David Attenborough), spiders do it too (in near-perfect fashion), and soil fungi weave mind-blowing mycorrhizal networks that connect and support trees and plants in ways that garner comparison to our own nervous systems and internet technology.

These examples, along with those from indigenous groups where weaving produces clothing, shelter, fencing, basketry, boats, netting and art, are what filled the mood board of my mind when I launched this project (don’t worry, that’s the first and last reference to mood boards in this newsletter). They inspired the basic definition of boundaries that I shared in the first Boundaries post: “If all truths are bounded, then boundaries are the membranes that allow truth to persist. Boundaries protect. They keep things alive.”

A newsletter called Membranes, by a physician no less, would have stirred up too many associations with the sticky, squishy, oozy membranes of the body, overly narrowing the concept and probably grossing out a few readers. (I’ll ease us into any discussions about mucosal tissues in the body—though I am brainstorming an upcoming post that will talk about skin, touch and physical contact: the neglected delicacies of this socially-distanced age.)

“Setting healthy boundaries” makes less sense in my playbook than weaving, tending and growing boundaries. “Setting firm limits”—like one would a fence, a deadline or a ground rule—is an apt turn of phrase. Knowing the difference is where the magic happens because boundaries and limits, like the trite but true powers of yes and no, work together. In matters of the human psyche, tending to the abundant boundaries in our life increases our depth of feeling and perception, whereas setting firm limits allows us to identify places where our ability to process feelings and perceive things truthfully breaks down. “Setting firm limits” makes sense because beyond these limits it becomes difficult or impossible to make sense of things. The experience of violence, trauma, abuse, and burnout can overwhelm, numb and even cut one off from their senses. My chosen profession of psychiatry first grew out of the work of 19th-century neurologists, who tried to understand the experience of patients who suddenly lost sensation or control of a body part without apparent injury or disease.

Without limits on our own and other’s behaviors (speech included, the Golden Rule generally applied), we lose a key distinction between the senseless and the sense-making. We lose a key to personal and collective creativity. An aphorism from the design world is that “constraints breed creativity.” Twitter’s character limit for tweets is an integral part of the Twitter-sphere’s feel and cultural impact. Dr. Seuss’s publisher challenged him to write a children’s book using only 50 unique words and he created Green Eggs and Ham (to boot, all but one of the words in the book are one-syllable). The difference between noise and music are the constraints of rhythm, melody and harmony.

Research on optical illusions (and some famous Las Vegas-based magicians that skillfully apply them) shows that humans suffer from many perceptual shortcomings, even in our supposedly “strongest” sense—vision. Yet, the researchers note, we have evolved “to be highly creative with our information inflow precisely because of how impoverished our sensory inputs are. Our survival as a species has long depended on a brain that can connect the dots not only in visual perception, but more broadly in our overall.”

If our senses weren’t so limited, magic would lose a lot of its power. Even if you’ve never been a sleight-of-hand fan, your enjoyment of concerts, museums, landscapes, meals and many other sensory rich experiences would be diminished without the need to anticipate and participate in “connecting the dots.”

The Limits of Our Imagination

As we’ve seen, even at the most rudimentary level of “making” sense—the neural programming of our five senses—limits aren’t limitations. Constraints are integral to our perception. Several levels up in the brain’s architecture, limits also liberate the imagination, giving it just enough ground to gain traction in an otherwise fluid stream of consciousness. By definition, imagination is the power to form a mental image or experience of “something not present to the senses or never before wholly perceived in reality.” Although we speak of some people as “creative” as though it’s a special attribute, optical illusion researchers disagree: “In the intricate, astonishingly rich world that all of us create from rough perceptual sketches, creativity is not an option. It is a neural imperative.”

To counteract the well-known downsides of this creativity—wide-spread conspiracy theories, blinding ideologies, and the power of charismatic storytelling over truthful contradictions—we need better science and better journalism. But we also need to include the creative arts in our understanding of critical thinking. Firing up the imaginations of entire populations, children to elders, could help break people’s unexamined allegiance to the world as it presently exists for them, stoking the possibility of awe-inspiring futures through art, fiction, fantasy, role-playing, and other non-rational pursuits that are rarely celebrated in today’s society, except for the few who manage to make artistic endeavors their full-time work. In his book From What Is to What If, author Rob Hopkins points out that in addition to social media’s disinformation problem, our politics and economy also create a “disimagination machine” whose effect goes largely unnoticed:

“We recognise that if a population isn’t sufficiently nourished, we will see a decline in health and a rise in preventable illnesses. We recognise that if we fail to give a population a good education, it will fail to reach its potential. Yet the neglect of the imagination is generally overlooked, seen as a frivolous distraction from the overarching aim of building economic growth and technological progress… our imagination isn’t accidentally dwindling; it is being co-opted, suffocated, corrupted and starved of the oxygen it needs.”

This perspective gives new meaning to Greta Thunberg’s famous statement to diplomats at a 2019 U.N. Climate Summit: “You have stolen my dreams.” Limitless wealth concentration and corporate expansion has stolen not just dreams, but the dream-making apparatus, which needs unstructured time and open, undisturbed space—the two basic dimensions that unfettered capitalism invades, commodifies and, ultimately, destroys.

Even with the system stacked against it, imagination perseveres. As a neuroscience nerd, practicing mental health specialist, climate activist, and sometimes writer and songwriter, my best work happens as I ride the neural imperative toward creativity. Good talk therapy takes lots of imagination to speak, think and feel in new ways, while respecting the limits that help differentiate it from the conversation you might have with a friend or mentor. An essay or song needs a structure and a word limit or time signature, with moments of tension and release amongst those elements. A sustainable earth system necessitates limits to growth, especially on extractive industries and their pollution, political influence and media manipulation. Yet for many people, it is more difficult or dangerous to imagine a future steady-state global order where economic growth is unnecessary for prosperity (the vision of many ‘de-growth’ activists and scholars) than it is to imagine different ways to get people into space and onto dustbowl planets like Mars.

Choose Your Own Carrot

Limits on economic growth and corporate influence are rebellious acts of imagination that would in turn spark many more. The prospect of a post-growth economy, where humans understand and live within the constraints of our surviving ecosystems and shared atmosphere, could lead to a resurgence of local cultures and services. Done correctly, economies would shift from mass production to a localized, less resource-intense focus on craft industries and the “caring” industries of child and elder care, education and health promotion. The recent release of the Biden administration’s American Jobs Plan (a proposed $2.25 trillion infrastructure and climate mitigation plan) and American Families Plan (a proposed $1.8 trillion health, child care and free community college plan) points toward a future where craft work, caregiving and education form the backbone of a thriving society. Both these plans are supported by more than 60% of Americans. Yet because they would increase tax revenue from corporations and ultra-wealthy individuals, they are vehemently denounced by Republican opposition, especially the climate change and caregiving provisions of the plans. And yet, due to looming demographic changes that will see global population begin to decline in the second half of this century, we have the opportunity to both leverage this population decline to help heal our severely-damaged earth systems and to manage the avalanche of elderly care that will be needed in aging populations.

The Biden administration plans, and any effective legislation to keep us from burning down or burning out, need to set limits and expand boundaries. This is a carrot-and-stick strategy that uses sticks to build fences rather than beat people and lets communities cultivate their desired rewards rather than planting the same carrots as far as the eye can see. Taxes, regulations and industrial standards can limit the behaviors and power of the billionaire class and the corporations it controls, while directing funds and decision-making power to cities, communities and companies that invigorate local cultures, work forces and supply chains. A ruling this week by a Dutch Court that instructs oil giant Shell to reduce its carbon dioxide more rapidly is the first of its kind in limiting the world’s largest polluters; it also calls into question the strategy of institutional investors and banks that continue to invest in fossil fuel companies despite these legal and financial liabilities. These large investors could divest from polluters and reinvest in community-driven sustainable industries. This vision, drawn from the teachings of bioregionalism, requires just a few key limits on the accumulation of capital and the use of natural resources to encourage an explosion of boundaries in our everyday lives. It promises an ebbing of corporate control over our agricultural, entertainment, clothing, manufacturing and transit systems after the king tide of American-style capitalism that has decimated so much unique cultural and physical infrastructure across the world.

Government-supported bioregionalism could reshape the map of how and where Americans live. Most importantly, it could change the “why” of American life. Beyond the binary of believing people either “work to live” or “live to work,” there is a future where work generally supports and sustains life on Earth. This is care work writ large, encompassing everything from caring for people from cradle to cremation to caring for forests, plains, seashores, wildlife corridors, farms and urban gardens. If you’d like to see this vision rather than just reading about it, I recommend an optimistic film, which admittedly avoids the political confrontations that are necessary for its vision to become reality. 2040 is directed by an Australian filmmaker who calls it a “visual letter to my daughter showing her what the world could look like that year if we put into practice some of the best solutions that exist today.”

Watch the trailer here, which includes an excerpt of an interview with Kate Raworth, a sustainability expert famous for her Doughnut Economy idea. In the trailer, Raworth states simply that “People want to be working on something that they can see is actually helping to regenerate the world.” Like our children, all of us need safe boundaries and appropriate limits. We don’t outgrow these needs. The regeneration of the world, whether in each new generation of humans or in the more-than-human renewal of whole ecosystems, is the art of getting limits and boundaries balanced and working together.

The Big Picture at a Personal and Planetary Level

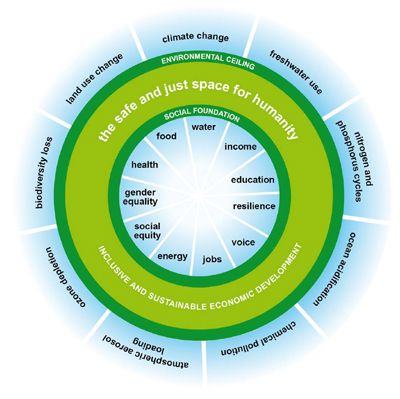

Let me offer two images to finish out this review of limits and boundaries. The first is from the aforementioned Kate Raworth and her 2017 book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. My wife and I both read the book; she said it could have been condensed into an essay. I thoroughly enjoyed the book even with its repetition (but then again, I have a vigorous appetite and resistance to satiety when it comes to doughnuts or books employing them as a metaphor for ecological salvation). But my wife didn't go far enough; the book can actually be condensed down to a single image, its titular Doughnut economy:

There are two limits in this image. One is the “Environmental Ceiling” (the outside of the doughnut) and the other is the “Social Foundation” (the outline of the doughnut hole). Limits on economic growth, capital accumulation and resource extraction create the Economic Ceiling, and should ultimately translate to limiting the effects of human activities on nine fundamental components of a healthy Earth, like freshwater use, biodiversity or ocean acidification (outer blue shading). The Social Foundation represents each human’s right to eleven fundamental components of a healthy, gratifying lifespan, including access to education, health care, gender equality and energy. The doughnut made by these two limits is where a healthy human civilization in balance with ecosystems can be sustained indefinitely.

The doughnut is a good summation of the ecological and social constraints that should unleash our collective creativity in this era of global instability, putting us back onto a path of global and hyperlocal renewal.

Yet our day-to-day decisions can’t possibly account for and integrate all nine pillars of the Environmental Ceiling and eleven columns of the Social Foundation. That’s the work of democratic movements and the collective action of governments. For personal use, there is an image that I find complements this world-spanning view. It circles back to the powers of yes and no that so much self-help motivation extols without contextualizing them in the reality of an entire planet imperiled by the poor limit-setting and rapacious boundary-breaking of extractive capitalism.

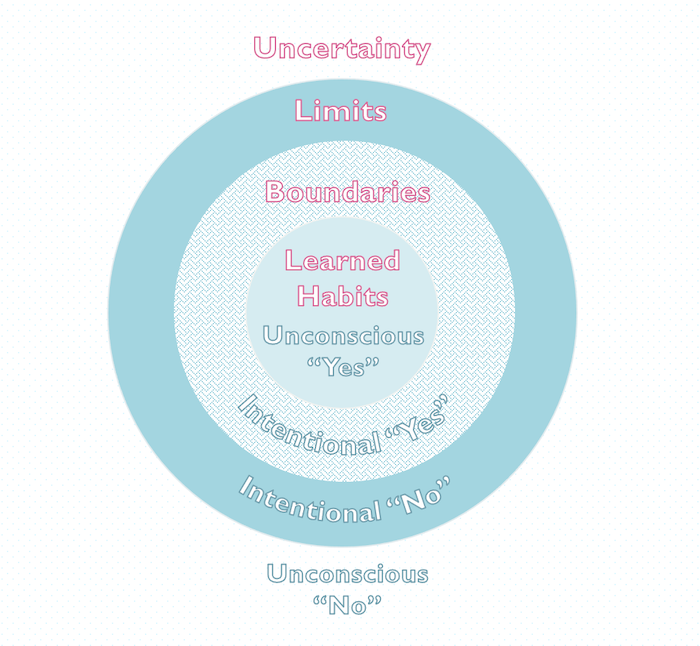

Here’s my condensation of the boundary/limit distinction I’ve been crafting here:

For most of us, our everyday state of being is defined by learned habits of thinking, feeling and acting that switch into gear the moment we wake up. Without much conscious will, we say “yes” to getting out of bed, doing our morning routine, picking up our phone, putting food to our mouths, and reacting to the day’s demands. Beyond these habits, we get only moments of truly intentional limit-setting and boundary-making. Sometimes the limits lead us: “I will not buy that,” “I will not eat that right now,” “I will not look at my phone while doing this.” Other times, the boundaries invite us: “I’ll look into that,” “I’ll reach out to that person,” “I’ll stand up for that value or principle today.” The times and places where we get to intentionally say yes or no are how we participate in the immense processes that ultimately sum to the blue-and-green doughnut diagram.

Beyond our limits is the limitless expanse of uncertainty. Uncertainty is not only a space of not-knowing, it’s the unknown or unconscious "no", wherein our imagination and understanding cannot penetrate a cloud of probabilities and chaotic energy that pass over and around us. This unconscious “no” may seem negative, but it's a double-negative, a space of potential, the source of learning and creativity that comes to life at our limits, within our boundaries, and beyond our habits. The celebrated intellectual and theoretical physicist Richard Feynman, in a letter of support for a female colleague who would later become Caltech’s first female tenured professor, wrote that “in physics the truth is rarely perfectly clear, and that is certainly universally the case in human affairs. Hence, what is not surrounded by uncertainty cannot be truth.” (italics mine)

I’ve made the boundaries and limits layers of this image wide enough to contain the intentional yes and no moments that arise each day. But some days, weeks and years feel like a big ball of learned habits, wrapped in thin, friable layers of intentional living. A doughnut economy would shore up these layers of limit-setting and boundary-making in ways that no amount of self-affirmation or self-help can summon. If we had true environmental ceilings, far fewer ultra-rich families and individuals would be mired in the aimless yet violent ennui of competitive “success” that gratuitous wealth promotes. These ceilings would, in turn, support universal social foundations, which would be actual livable conditions, rather than social “safety nets” that sometimes catch people in free fall but rarely provide a basis to live. There would be no limitless success and there would be no boundless misery.

The doughnut and the habits/boundaries/limits “jawbreaker” are simplifications of reality. Uncertainty abounds and courses through all our lives, no matter how comfortable. The larger the map, the less details about the journey to a destination that it can provide. Now that I’ve put together two introductory posts about my fascination with Boundaries, we’ll be stepping off the map and onto the trail to look for stories where boundaries are being formed real-time in the world today. With that in mind, keep an eye out for forthcoming posts about hedgerows in Britain, intergenerational relationships and the rage that can bubble up within them, and the functions of skin and touch in sensitizing us to the boundaries that keep us alive.

Cheers ~ Alex